03 Sep The demon drink: war on sugar

Our addiction to sugar is linked to obesity, cancer and heart disease – and soft drinks are among the worst offenders. Alex Renton reports on the new health war, and reveals why some fruit juices may be as bad for you as cans of fizz

The tin of 7UP rolls to a stop at my feet. I pick it up, scowling at the kid on a bike who’d tossed it and missed the litter bin. The can is green and shiny: “Put some play into your every day,” it says. “Escape to a carefree world… Don’t grow up. 7UP.” And underneath, in tiny print, the real info (though you need a calculator to get to the truth): the lemon- and lime-flavoured drink contains a trace of salt, no fat, no fibre and 34.98g of sugar – eight teaspoons – and 135 calories. That’s enough energy for about 15 minutes’ cross-country running. It’s cheap, too. Half the price of milk.

If the stats are right, this teenager in Leith, who threw the empty tin, drinks 287 cans, or the equivalent, a year: more sugary drinks than any other child in Europe. Not to mention a whole lot more sugar, in breakfast cereals, bread, and even chicken nuggets. That is in part why Scottish children’s teeth are the same quality as those of children in Kazakhstan. And perhaps why a 2010 survey of 17 countries found that only Mexicans and Americans were fatter than Scots.

Of course sugary drinks make work for more people than dentists. Though the drinks and food industry still hotly contests it, a scientific consensus is now emerging that fatal problems can be traced back to excessive sugar consumption. Sugary drinks, addiction and obesity are inextricably linked: excess sugar in the diet may be a greater cause of obesity than fat is. Obese people suffer from diabetes, cancer, fatty liver disease, dementia and heart problems to the extent that their healthcare costs are double those of people with a healthy body mass. The “metabolic syndrome” maladies associated with insulin resistance and obesity – many authorities now just use the term “diabesity” – are expected soon to overtake tobacco as the leading cause of heart disease in the world. And perhaps of cancer, too.

Thus the “don’t grow up” line on that 7UP tin carries a grinding irony. Dr Robert Lustig puts it brutally: “The numbers don’t lie… as a rule, the fat die young.” He is a medical doctor and professor of clinical paediatrics at the University of California who has emerged as the guru of an increasingly noisy international campaign pressing governments to act as aggressively on sugary drinks as they have on tobacco. The two are seen as directly analogous – unnecessary habits that cost people and society dear. Lustig believes that children are at the forefront of the sugar-driven health crisis because soft and fizzy drinks are the most efficient way of delivering this “poison”. His word.

So the 7UP tin is quite an artefact. It shows capitalism at its most efficient and rapacious: where ingredients – sugar, flavouring, water – costing almost nothing can be turned into a profit margin measured in the thousands of per cent. It illustrates the extraordinary diversion of farmland and forest into the production of the almost useless while nearly a billion people on the planet are starving. The can is an icon of the key dietary changes of the era, where we upped our simple carbohydrate intake – sugar – to the point that it started harming us in ways never seen before.

A monumental battle is just beginning between the sugar and food corporations and governments, which know that society can no longer bear the strain of the polysaccharide habit. If the 40 years of war between government and Big Tobacco are anything to go by, the fight will be dirty.

It’s a feature of modern life that the young have started getting the diseases of the old – problems with their hearts, their livers, cancers, diabetes and so on. That this may be triggered by the changes in our diet has been known for at least 60 years. During the Korean war, US army surgeons got a chance to do something unusual: perform autopsies on lots of young people. These found plaque in the American casualties’ arteries – even among the teenagers. But there were no blockages in the hearts and valves of the youthful Korean dead. At the time, this bizarre phenomenon was ascribed to the fat load in the GIs’ diet. But Americans who fought in Korea and Japan were fuelled by Coca-Cola and its rivals; and modern analysis now concludes that sugary drinks may have been the villain.

Most rich nations saw their sugar consumption increase by 30-40% between 1970 and 2000. In Scotland it quadrupled in 60 years. A key moment was the introduction of “high fructose corn syrup” (HFCS) – a fantastically cheap sugar made from America’s surplus maize (in Europe we manufacture something similar from sugar beet). American government subsidy for the corn farmers – and high taxes on imported sugar – made the product cheap and attractive. Though there were issues around taste, in 1980 Coca-Cola successfully switched to using HFCS. After water, sugar is, of course, the major ingredient in its product. Profit margins improved, and Coke’s rivals soon jumped aboard.

king the can: teenagers in Scotland drink an average of 287 cans a year – each containing eight spoons of sugar. Photograph: Nathalie Louvel/Getty ImagesIn the UK we eat and drink around 70% more sugar than the government says we should, and the obesity figures have been fairly stable since they peaked in the early 2000s. (Though with 30% of under-15s overweight, and consuming sugar just like adults, the epidemiologists are predicting the obesity rate to rise.) But our sugar consumption peaked in 1982 and the soft drinks manufacturers say that now 40% of carbonated drinks contain “no added sugar”. Why, then, have obesity rates not plunged?

I found at least a piece of the answer to that at breakfast in my house, when a family with two young, and I think we’ll say “sturdy”, children came to stay. Just a touch self-righteous, they spurned the low-sugar cereals – Weetabix, porridge – that our children eat. Instead they got busy with the blender, making vast watery smoothies with fruit juice, apples and bananas. But the supermarket apple juice, I pointed out, contained 35g sugar – as much as a can of Coke. And a ripe banana has four teaspoonfuls of sugar. “That’s natural sugar. It’s fructose. That means it’s from fruit,” I was told.

The truth is that, though consuming sugar along with the fibres of fruit is better than without, these middle-class healthy drinks may be higher in sugar than the Ribena my mother was fooled into giving us children for our health. And that, too, had more sugar in it than Coke.

Sugar is sugar – a simple chemical, and it makes little difference whether it’s crushed from an organic, hand-picked fruit or fracked in a factory out of corn and beet. And fructose is just another of the monosaccharides that make sugar, though it’s the one with a friendly Latin-derived name. In fact fructose is the key to all sugar – it makes it taste sweet. Table sugar is half glucose, half fructose. The high-fructose syrups the drinks manufacturers use are probably – they won’t say – made of 55% fructose: more sweetness for the sugar load.

Many scientists have marked fructose as the ring leader in the team of monosaccharides. Lustig, who likes to turn a phrase, calls it theVoldemort of sugars – and it is biggest in the sugar load of soft drinks.

A 240ml glass of orange juice might contain 120 calories of sugar, or sucrose; half of that will be fructose. The fructose will all end up in the liver, which may not be able to metabolise (process) it fully, depleting vital chemicals in the organ and turning into fat. “It’s not about the calories,” says Dr Lustig. “It has nothing to do with the calories. It’s a poison by itself.”

What is undeniable is that problems in the liver in turn contaminate and disable other systems, including the insulin production of the pancreas. The effects are felt ultimately in the heart, the immune system and by producing cancers. Insulin resistance may also be a player in dementia.

“Fructose can fry your liver and cause all the same diseases as alcohol,” Dr Lustig continues. Key to the obesity debate is the charge that high insulin levels interfere with the hormone leptin, which is a signalling device that tells the brain when we’ve consumed enough. So you drink or eat fructose, and then you want more food. Sugary soft drinks deliver the fructose fastest to the organs that can’t handle it. And, of course, they are largely consumed by those most vulnerable to diseases: the poor and the young. For children, every extra daily serving above the average increases the chances of obesity by 60% .

weet success: we consume 70% more sugar than the government’s guideline figure. Photograph: Ryann Cooley/Getty ImagesThe drinks industry and its science do not agree. Gavin Partington, the energetic director general of the British Soft Drinks Association (BSDA), says: “A calorie is a calorie.” Dealing with the fat crisis is about helping people to use up those calories through exercise.

Across America though, health authorities appear to be coming round to Lustig’s view. Should we? I put that to Professor David Colquhoun of University College London, a specialist in toxicology and a scourge of cod science through his Improbable Science blog and gloriously cantankerous tweeting. Does he buy the anti-fructose lobby’s theories? “Bugger all is known with certainty about the effects of diet on health. That’s why so much is written about it. The whole problem is that it’s all correlational stuff – there’s no causality proven. Nevertheless the best current guess is that sugar is a much bigger problem than fat. And it’s addictive, which is why manufacturers do it (I’ll happily eat a whole bag of jelly babies). That can’t be good – so, yes, I’d say let’s tax it.”

Punitive taxation on sugary drinks – already in place in some European countries – will be a long while coming to Britain. The nutritioncampaigners Sustain and 61 other charities and health organisations, including the Royal Society for Public Health, called on the chancellor to introduce a “sugary drinks duty” of 20p a litre in this year’s budget. It would raise £1bn a year – some of which, they suggested, could usefully be spent on children’s health and free school meals. George Osborne stayed quiet; health secretary Jeremy Hunt said he was sceptical. Far more influential than Professor Colquhoun, Lustig and any eminent academic is the food and beverage industry. And that is, of course, busy leaning on the government to avoid any further tampering with its right to flog sugary drinks as healthy.

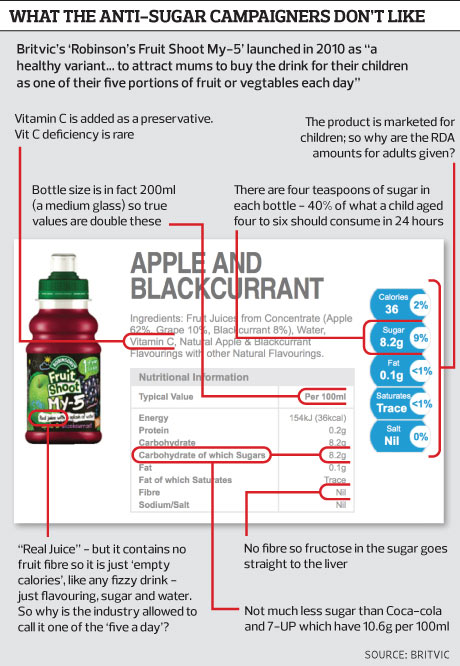

The BSDA, to which manufacturers such as Britvic and AG Barr hand queries, has stopped insisting that there is no proven link between sugar, soft drinks and obesity – its position until a few years ago. (This stonewalling claim is still the position of Associated British Foods, supplier of half of the UK’s sugar.) Now the defence centres on the “unfair cost” to shoppers of a tax, and the 9% fall in sales, over the past 10 years, in added-sugar drinks. “Sixty one per cent of soft drinks now contain no added sugar,” they claim. But the BSDA’s stats are dubious: for a start, they include 2bn litres of bottled mineral waters – 15% of all soft drinks. And, of course, the carton juices contain “no added sugar” – but as we’ve seen, many have as much sugar in them as Coke.

But there are extraordinary things going on in America, for which Lustig – and his 3.6m-hit YouTube film Sugar: The Bitter Truth – can take some credit. More than 30 state and city legislatures, from Hawaii to New York, have discussed or proposed curbs on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) ranging from bans in schools to cuts in portion sizes and a sales tax. New York’s mayor, Michael Bloomberg, has proposed removing SSBs from state food assistance programmes. He is currently fighting a legal battle to enforce a city-wide ban on “supersize” servings of sugary drinks. But petitions against the ban have gathered more than half a million signatures.

Back here in Leith the empty Irn-Bru, Fruit Shoot and Red Cola bottles glint in the grass around our local park. The local Italian ice-cream shop is selling Irn-Bru sorbet. You can get six litres of high-sugar drinks for just £2 down the road in Iceland. That’s just 50p to put an adult into Lustig’s fructose danger zone. What’s wrong with water, asks Annie Anderson, professor of public health nutrition at Dundee University. “We need to promote water drinking: it’s cool, refreshing, thirst-quenching and healthy!”

We’ve always taken a lot of sugar in Scotland. Our grandparents put sugar-ally sticks – liquorice and molasses – under the bed in a bowl of water overnight (next to the bedpan), to drink the pale brown brew first thing in the morning. The journalist Audrey Gillan, who grew up in a Glasgow housing scheme, remembers the visits of the “gingers” van, delivering bottles of limeade on credit, like the milkman. Workers in the Clyde shipyards were proud to be fuelled on “lemonade and a jilly piece”: sugar, then and now, is cheap energy for the poor, and it still provides nearly 20% of Scottish calorie intake for adults and children. Though the percentage is dropping slightly, it’s still nearly twice what it should be. According to the historian and nutritionist Maisie Steven, Scots kids eat four times the amount of sugar they did in 1942.

Up the road in Fife, farmer Mike Small has high hopes for the campaign for a Scottish tax on SSBs: he and his sustainable food campaign, the Fife Diet, will launch a new manifesto for it in September. “It’s going to happen, because it’s just so bloody obvious. There was a report just last month from Scottish doctors saying that type 2 diabetes has doubled. They’re amputating limbs from people in their 20s.”

Forms of SSB tax have already started in Denmark, France, Finland and Hungary. Scotland, Small says, is in the mood to follow. “There’s an opportunity. The Scottish government is in the right frame of mind for doing stuff that’s about regulatory control, rather than soft policies for behavioural change. Because those just don’t work with tobacco, alcohol and sugary beverages. These are addictive substances.” And the soft drinks industry’s defence? “Propaganda to blanket their profiteering – profiteering that causes illness like diabetes. Unforgivable.”

The Scottish government is – I’m told – considering a tax on sugary drinks. But first it has to conclude a battle over a minimum alcohol price (an idea of David Cameron’s that he has already dropped). It’s been held up in the courts for two years, the fight led by the Scotch Whisky Association – which, apart from its worries about jobs and profits, has a core belief that states should not be able to tax companies punitively on health grounds. And that is the heart of the matter.

The story behind the label. Composite: ObserverAlex Renton’s forthcoming ebook, Planet Carnivore, will be published by Guardian Shorts on 26 August. Find out more at guardianshorts.co.uk

The story behind the label. Composite: ObserverAlex Renton’s forthcoming ebook, Planet Carnivore, will be published by Guardian Shorts on 26 August. Find out more at guardianshorts.co.uk

The truth about fruit drinks: Q and A with Britvic

Why is the GDA info in a product that appears to be aimed at under-18s given in adult quantities?

Last month, Britvic signed up to the Department of Health’s new voluntary Front of Pack Nutrition labelling scheme. As part of this, and in line with the new European Regulation on the provision of food information to consumers (EU FIC), the Reference Intakes (RIs), formerly know as Guideline Daily Amounts (GDAs) used on front of pack must be those set out in the regulations. As there is currently no provision in the regulation for the use of Children’s RIs, adult values must therefore be adopted. The information displayed on the Britvic.comwebsite is correct according to the new nutrition-labelling regulations. We intend to update all product labels by December 2014, which is the deadline for compliance to the EU FIC regulation.

On what basis does a drink containing no fibre claim to be fruit juice?

Fruit Shoot My-5 meets the definition of a fruit juice drink as set out in the Fruit Juices and Fruit Nectars Regulations, 2003. Due to the manufacturing processes used to create a fruit juice product, the fibre content will be less than that found in the physical fruit itself. As a result of this, and the naturally containing sugars found in fruit juice, fruit juices can only count as one portion of the recommended five portions of fruit and vegetables a day.

And, given that, why is it so vividly billed as My-5? Does that mean it is a 5-a-day drink, and how do you justify that?

Fruit Shoot My-5 can count as one portion of the recommended 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day, which is a standard term used widely throughout the business. More information about 5-a-day can be found here. A 150ml portion of 100% fruit juice counts as one portion of your 5-a-day. Fruit Shoot My-5 contains at least 80% fruit juice and therefore provides at least 160ml of fruit juice in each 200ml bottle.

Is the Vitamin C added?

Yes, Vitamin C is added to Fruit Shoot My-5.

What proportion of the sugar is fructose in the product?

Fruit Shoot My-5 contains no added sugar, only naturally occurring sugars from the fruit, a proportion of which will be fructose.

• This article was amended on 4 and 5 August 2013. The original version wrongly stated that 135 calories were enough for an hour’s cross-country running; this has been corrected to about 15 minutes. in addition, references to 35% sugar, rather than 35g, or “high sugar”, and “more sugar than Coke” rather than as much sugar as Coke, have also been corrected.